Deborah Hutton

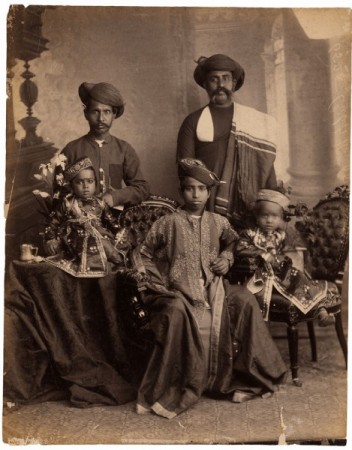

Cat. 17. Raja Deen Dayal. The Maharaja of Ajaigarh with his Three Sons.

Bundelkhand, Central India, circa 1882.

Albumen print

The backs of the cartes-de-visite produced by Dayal Studios in the early 1890s proudly proclaim in bold typeface, “Landscape and Portrait Photographer, Lala Deen Dayal, Indore C.I. and Secunderabad, Deccan.”i Indeed, although Deen Dayal (1844-1905) captured a wide range of subjects over the course of his nearly thirty year career as a photographer, he is perhaps best remembered for two subjects: his luminous landscape and architectural views, on the one hand, and his refined portraits of the Raj’s upper echelons, both British and Indian, on the other. The seven photographs of South Asian rulers, courtiers, and upper-class men included in this exhibit provide us with exquisite examples of Dayal’s early portrait photography. Taken together, the images demonstrate how his portrait photography developed during the first half of his career, between circa 1878 and 1894.

Dayal first took up photography sometime around 1874 while working as a surveyor for the Public Works Department of the Central India Agency in Indore. It seems to have only been a side activity at first; he didn’t start employing photography in his professional surveying work or assigning negative numbers to his images until around 1878. Over the next several years, his photographic output increased. As he traveled around Central India through the territories of Gwalior, Dutia, Punna, Rewa, Ujjain, Mandu, Jhansi, Orchha, etc., he assembled a series of carefully composed views of each region. He photographed landscapes, railways, palaces, historical monuments, and the local rulers with their attendants. Many of these images were included in leather-bound albums that continued to be produced and sold through the 1890s.ii

Five of the portraits here (cats. 15, 16, 17, 18 and 19) seem to be from this early period of his career, based on the subjects and the negative numbers recorded on the photographs. More specifically, they probably date to circa 1882, when Dayal employed negative iii numbers ranging from the 1000s through 1400s. cat. 17, the negative number “1289” appears in neat white numbers on the dark carpet near the feet of the sitters. That photo depicts Sir Rajnor Singh (b. 1848, r. 1859-1919), the Maharaja of Ajaigarh, with his three sons, Jaipal, Bhopal, and Pakshapal. Ajaigarh was a princely state in the Bundelkhand Agency of Central India best known for its hill-fortress, which Dayal also photographed. Dayal spent part of 1882 traveling through Bundelkhand with the colonial administrator Sir Lepel Griffin on a photographic tour, thus it makes sense that he would have photographed the Maharaja of Ajaigarh that year. Likewise, cat. 15 depicts Sir Pratap Singh (b. 1854, r. 1874-1930), the Maharaja of Orchha, another of the princely states in Bundelkhand whose architecture Dayal documented. This portrait, which depicts the maharaja seated on a pillow and flanked by flywhisk-bearing attendants, has the negative number 1261 written beneath the ruler’s right hand.

It should be noted that two of the images (cats. 16 and 18) appear to have negative numbers in the 200s (284 and 268 3⁄4, respectively), which would date them earlier than 1882. However, most likely the initial “1” had rubbed off the glass plates before these prints were made and their actually negative numbers are in the 1200s, like the other portraits. Because the negative numbers were added with dark paint onto the glass plate negatives after development (the dark paint appears white in the corresponding prints), they could be deliberately removed or just fade away over time. It is not uncommon for partial negative numbers to survive. Thus, although the negative numbers that appear on many of his prints provide an excellent way to date Dayal’s photographs, they do need to be carefully studied and taken in context. In the case of cat. 18, an unidentified group portrait featuring ten men and a young child, the number “1268” written on the mount beneath the photograph seems to confirm its dating to 1882. In cat. 16, which depicts the Maharaja Bhan Pratap Singh (b.1842, r.1847-1899) of Bijawar and his court, the signature in the lower right of the picture, “D.D,” again seems to confirm an 1882 date, as Dayal repeatedly changed his signature in his first few years as a photographer. He went from Deen Dyal to D. Dyal to D. Diyal to eventually D.D before forgoing a signature altogether.

Cat. 19. Raja Deen Dayal. A Young Prince Seated. Bundelkhand, circa 1882.

Albumen print, 20 x 13.5 cm

All five images demonstrate Dayal’s early approach to portraiture. They are taken outside, often in the palace courtyards of the nobility being photographed.

In the Maharaja of Orchha’s portrait, the surrounding buildings and treetops are reflected in the shield he holds. While in that image, the ruler sits on pillow in the traditional South Asian manner and the palace façade is visible behind him, in most of the portraits, the figures are seated in chairs, and dark cloth is hung behind them to create a backdrop. The ground is typically covered in carpets, often with a fine piled carpet or two placed on top of dhurries, the striped flat-woven carpets used out-of-doors. For portraits of just one or two people, such as cat. 19 depicting a young nobleman, the camera is situated close enough to the sitter to obscure the set up and thus makes the photograph appear no different than if it was taken inside a studio. In contrast, in the larger group portraits, such as cat. 16, the camera frame goes beyond the span of the backdrop, revealing the surrounding architecture.

While producing these early images, Deen Dayal continued to work as a surveyor for the Public Works Department of the Central India Agency. Finally, in 1885 he took a two-year “furlough” from his position in order to travel and focus on his photography. Because of the success he quickly achieved, he never returned to the PWD; however, he did maintain a connection with Indore, where he had at some point opened a commercial studio, the exact details of which are still murky and await further research.

In 1887 after receiving appointments to the Viceroy Lord Dufferin and the Commander-in-Chief Sir Frederick Roberts, Dayal travelled south to the Nizam’s Dominions of Hyderabad. There he photographed the military exercises held in Secunderabad as well as the historic sites and notable landscapes in and around Hyderabad. He also took portraits of many of Hyderabad’s notable figures, including the Nizam, whom he would photograph many more times over the years. In early 1888 he travelled northward to document another camp of exercises, this time in Meerut, 43 miles northeast of Delhi. From there, he travelled to Cawnpore, Lucknow, Sarnath, Banares, and other important sites around north India before returning to Hyderabad in September or October of that year. If the number “4241” written on the mount of cat. 20 is in fact the photograph’s negative number, then that would suggest this image dates to sometime between the fall of 1887 and the end of 1888; however, exactly when or where it was taken, as well as who it portrays, remains elusive. Interestingly, a glass plate negative of a somewhat similar portrait bearing the negative number 4243 survives in the collection of the IGNCA.iv In that image, a young Sikh gentleman (as opposed to the older Muslim gentleman in cat. 20) sits on what looks to be the same chair or an identically designed one as in cat. 20, but now situated in front of a patterned backdrop rather than a plain one. Both figures are positioned at almost exactly the same distance and angle from the camera lens, and both have one arm resting on the chair and the other hand on their lap, allowing the sitters to have a natural, yet still clearly formal pose.In contrast to the seemingly temporary and simple studio settings of cat. 20 and the IGNCA image, with their cloth backdrops and single chair, the setting of cat. 21 is clearly that of a well-to-do commercial studio. Specifically, this image was taken circa 1894 at Dayal’s Indore studio and depicts three young Central Indian princes, perhaps from Gwalior, with two attendants. The same painted backdrop, patterned carpet, and elaborate Victorian furniture appear in many of Dayal’s Indore studio images from the 1890s.v The lavishness of the studio setting speaks to the success that Dayal had achieved by that point in time.

Cat. 21. Raja Deen Dayal. Three Young Princes with Attendants.

Indore, Central India, circa 1894.

Albumen print 28 x 21.5 cm

In the fall of 1888 Dayal returned to Hyderabad, with, it seems, the intention to settle there. Within a few months he had opened a commercial studio in Secunderabad. By 1892 he was doing well enough to move his studio to a bigger and more prominent location in the city and was employing a large staff, including other photographers. He also continued to run the Indore studio, although that seems to have become less and less active as his Secunderabad practice grew. In 1894 Deen Dayal was appointed the official photographer to the Nizam of Hyderabad, an honour that came with a monthly salary and the title of “Raja Musavvir Jung.” Based on the surviving photographic evidence, it appears that the Indore studio may have closed shortly after Dayal received this new position. Thus, cat. 21 probably was taken in the last year or so of the Indore studio’s operation, based on its negative number, 6525, which appears written backwards on the right edge of the picture.

Of course, the closing of the Indore studio was not the end of Dayal’s portrait photography. If anything, studio portraiture became an increasingly important part of Dayal’s photographic practice. The Secunderabad studio continued to flourish, and in 1897 he and his sons opened another studio in the fashionable fort district of Bombay. During the decade before Dayal’s death in 1905, not only did the number of portraits that his studios produced grow, they also encompassed an ever-widening variety of sitters. The seven portraits included in this exhibition provide excellent examples of how Dayal’s portrait photography began in Central India and quickly developed alongside his unparalleled career.

i. For example, this backing appears on a carte-de-visite dated to 1894 and now house in the Alkazi Collection of Photography (ACP 98.60.0022).

ii. Many Dayal albums with the title “Views of Central India,” or something similar, survive. Most feature primarily his architectural and landscape views. An album (IOL Photo 1000/16) in the British Library containing photographs of Central India by both Deen Dayal and Henry Cousens is perhaps particularly relevant to the images here; it contains a number of group portraits, many of which date to 1882 and depict the same subjects as featured in these photographs.

iii. For a more complete discussion of Dayal’s use of negative numbers and their dating, see Appendix A of the forthcoming book, Deen Dayal: Vision, Modernity, and Photographic Culture

in Late Nineteenth-Century India, co-authored by Deepali Dewan and myself and published

by The Alkazi Collection of Photography and Mapin. All details regarding negative numbers, signatures, dates, and photographic techniques, as well as Dayal’s travels and career trajectory, are based on primary data that Deepali and I collected during a decade of research at archives throughout the U.S., U.K., and India.

iv. IGNCA # NBJ-2764n. In the IGNCA glass plate, the negative number appears on the image itself, written near the right edge of the chair. On the one hand, based on the similarities between the two portraits and the proximities

of the numbers, the IGNCA image seems to confirm that the number on the mount of cat. 20 is indeed its the negative number. On the other hand, the fact that the negative number of the IGNCA image is 4243, the exact same number that appears on the mount of cat. 21, whose actual negative number is 6525, suggests that perhaps the number on the mount of cat. 20 is not its negative number.

v. Several similar portraits survive in the collection of Dayal material in the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, Massachusetts (Ph81). One image in particular, numbered 6347, is worth noting, as it depicts a merchant from Gwalior and his two sons and is dated to 1894. The merchant wears a very similar turban to that worn by the two attendants in cat. 21.

If you would like to stay up to date with exhibitions and everything else here at Prahlad Bubbar, enter your email below to join our mailing list