Exhibition images

1/5

A Brass Incense Burner

Deccan, Sultanate India, late 15th early 16th century.

Brass. Height 30cm.

Published:

Zebrowski, Mark. Gold, Silver & Bronze from Mughal India. 1997, page 94, plate 87.

“The peacock was a popular motif in all periods of Indian art. A large incense burner in the shape of this proud bird strikes a remarkable balance between the abstraction of Islam and the sculptural qualities of the Indian tradition. Made of thickly cast brass, now covered in a rich black patina, the body and neck are pierced with large holes for the escape of the sweet-smelling smoke. The comma-shaped curls on the back, tail and crest indicate a southern origin. Similar peacocks prance upon the step-risers of the fantastic Throne of Prosperity represented in the Nujum al Ulum, an astrological manuscript dated 1570-1 which, according to a note written with the text, is known to have been in the royal library at Bijapur. Since this particular shape was obviously well defined by this date, and its vigorous design shows little of the naturalism associated with Mughal taste which began to affect Deccani art in the late sixteenth century, we can confidently assign it an earlier date, in the late fifteenth or early sixteenth century.” Zebrowski

Flowers and Geometry: Indian, Islamic and Himalayan Art

19th October, 2018 - 22nd November, 2018

Asian Art in London

1-10 November 2018

Monday-Friday, 10.00-18.00

Saturday 3rd November, 10.00-18.00

Sunday 4th November, 10.00-17.00

Saturday 10th November, by appointment only

Mayfair Late Night

Monday 5th November

18.00-21.00

The objects selected here transcend and go beyond their utilitarian function: Each image, object, artefact has a material quality or trace, however it also has symbolic meaning, a ‘raison d’être’ that transcends its function.

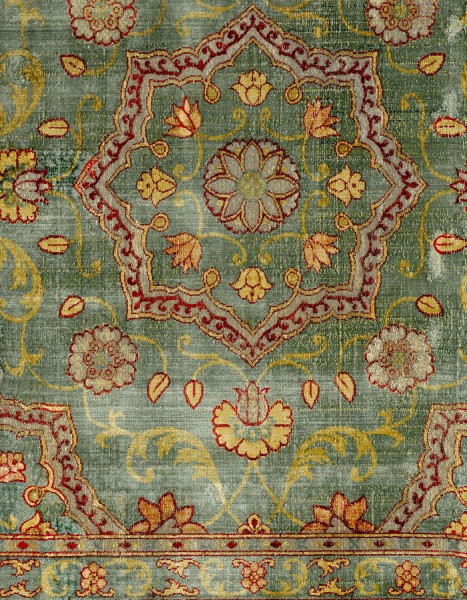

In the ancient cultures of Asia, ornament, patterns, symbols, flowers, geometric forms found on everyday objects, textiles and architecture stem from meanings in religion and literature, and have layered references. These forms take on a fascinating evolutionary journey through China, Iran, Central Asia and India.

Trade and travel allows for floral and geometric motifs to proliferate through a territory that is vast, spanning from Spain to China. Indian artists, artisans and patrons with keen sensibilities adapt and evolve ancient motifs of Primitive, Buddhist and Hindu origin with Islamic, Chinese and European styles to create marvellous and luxurious hybrids. An aesthetic and design evolution is manifest in the arts of the region from the past two millennia and more.

Geometry, theoretical and practical sciences and mathematics were widely understood and applied in ancient and medieval India, the Architectural wonders stand as testimony. Geometric design is the basis of Ornament and floral design, however with the advent of Islam it takes on a new, central role and flourishes.

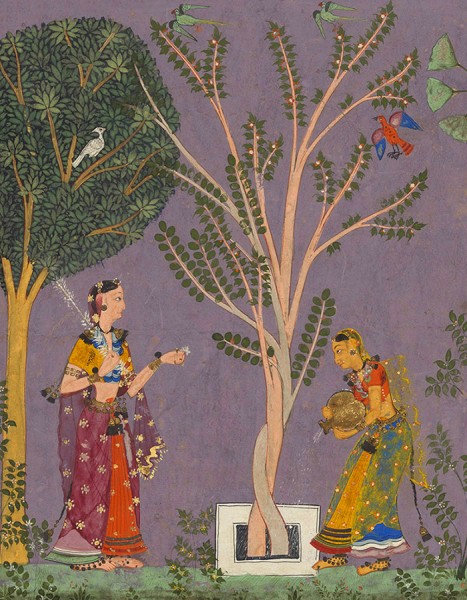

Ancient manuals, manuscripts and scrolls dedicated to the subject of Islamic design see them in a spiritual and cosmological context. They ascribe symbolism and see numerological significance in patterns. According to this theory the purpose of Islamic geometric design is to raise spiritual understanding through contemplation of its complex patterns. There are conceptual, and cross-geographical notions embedded in the techniques themselves, adding yet another layer of significance and history. The masterpiece of needlework design on a Deccani Royal canopy illustrates the perfect synthesis of Timurid, Ottoman and Indian styles.

Art and science bisect again through the realm of psychology in the poignant detail and expressions in Indian paintings, making them a barometer, mirror of society of their time. Sometimes read as simplistic, these are greatly more nuanced than they appear on face value. I continue to love Indian paintings, the intense, intimate worlds they communicate, where a painted flower can have the perfume of a real one.