Joachim K. Bautze

“Whoever has seen the palace of Boondi, can easily picture to himself the hanging-gardens of Semiramis” (James Tod [1782-1836] on September 13th, 1830 as quoted from the 2nd volume of his Annals and Antiquities of Rajast’han or the Central and Western Rajpoot States of India). “Whoever has seen the Palace of Boondi can easily picture to himself the hanging gardens of Semiramis” (Rudyard Kipling [1865-1936] quoting James Tod in the first volume of his From Sea to Sea and other Sketches). [Fig 1]

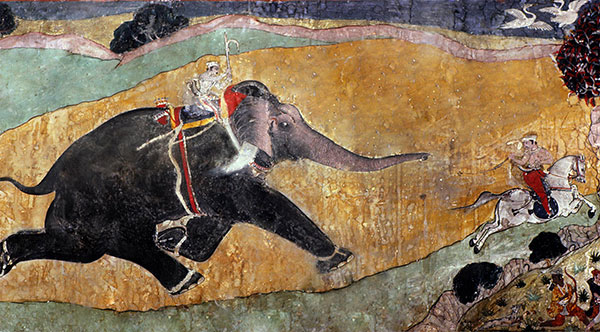

Figure 1. Wall painting in the Badal Mahal circa 1600-25, Bundi Fort. Rajasthan. Opaque pigments on fibrous ground prepared with lime.

Bundi (Formerly “Boondi”, also: “Boondee”) is the capital of the former kingdom of the Haraclan, situated in zila Bundi, Rajasthan, India. As Kipling already observed, the palace itself “is the work of many hands”. In fact, it was built over a period of several centuries and almost each ruler added another structure, many of which are decorated with wall paintings. Of these, the best preserved and most spectacular are in the so-called “Badal Mahal” (lit.: cloud palace). Although painted more than a century later, several people called it the “Sistine Chapel of India.” An American psychiatrist recently wrote about his experience when seeing the murals for the first time: “It was dark inside but, when hand-held lights illuminated great 17th century wall paintings, I felt like the first person to enter King Tut’s tomb.”

The “Baddal Mahal” in the spelling of the poet and historian Suryamalla Mishran, was built during the reign of Rao Bhoj, who became king at about the same year his father and predecessor, Rao Surjan (r.1544-1585), died. It was under Rao Bhoj (r.1585-1608) that one of the finest styles of Rajput painting, the Bundikalam, was initiated by Mughal artists working in Chunar, the famous fortress situated on a peninsula in the river Ganga, in 1591. The murals within the Badal Mahal, however, do not immortalize the life of Rao Bhoj, but of his eldest son, Rao Ratan (r.1608-1631).

Without being compelled to the degrading custom of sending a dola, i.e. to give Rajput women to the Imperial harem, Rao Ratan became a privileged and hence most loyal appointee to his suzerains, the Mughal emperors Jahangir (r.1605-1627) and Shah Jahan (r.1628- 1658).

Already in 1608, the emperor Jahangir received three elephants from Rao Ratan, one of which the former “much approved.” He called it “Gajratan” (lit. “elephant jewel”, alluding to the name of its donor, Rao Ratan) and ordered it to be painted. The painting is now kept in the Indian Museum, Calcutta/Kolkata, I.M. no. R.647/S. 77. Besides, Rao Ratan moved into battle on an elephant. It was called “Light of the world” (Jagajot). Were it not for these historical references, the predilection for this animal on the side of the Hara-rulers would also be well testified by numerous wall paintings, drawings as well as miniature paintings.

A comprehensive description of the paintings within the Badal Mahal cannot be given in a few lines. Besides, this was already done in various books and a series of scholarly articles more than two decades ago, particularly during the “Festival of India” 1982 in London. Suffice to say is that the entrance to the Badal Mahal is marked by a kind of porch in the centre of the southern wall. The room as such measures 7,41 m from East to West and 4,20 m from North to South. Like most painted premises in Rajasthan, it can be divided into 5 horizontal layers, the lowermost one (A) being without any figural wall paintings in the first third of the 17th century. The second level (B) from the bottom is normally at eye level. In the Badal Mahal, however, it is slightly above eye level, starting at a height of 1,42 m above ground. This second level contains a complete sequence of 36 Ragamala paintings, following the so called “Painter’s system” in the Bundi variety. Neither the first nor the second level contain any historical paintings, which are mainly represented in the third level (C) which has its lowest border about 2,45 m above the floor. This layer consist of an uninterrupted band measuring 56 cm in height and represents the sports and favourite pastimes of Rao Ratan and his relatives. This band measures roughly 23,20 m in total length and shows various elephant fights, a procession of elephants, an elephant chasing a horseman, various huntings scenes and polo.

The fourth layer (D) is the transitional zone between the perpendicular wall and the ceiling (E) which consists of a central dome flanked by two half cupolas resting on squinch nets. This fourth layer literally raises Rao Ratan to the height of Krishna, Rama, Europeans in the fancy of the Indian artist and the hero Madhava from the then popular love story by the poet Vachaka Kushalabha, the Madhavanala-Kama- kandala-chaupai. Surrounded by his court, Rao Ratan is shown in a kind of Darbar-scene on the Western wall looking at a miniature painting presented to him by one of his artists [see fig. 2]. The miniature shows an elephant mounted by a mahavat and strongly resembles an often published painting in the Museum of Islamic Art, Berlin, which is signed by the artist Zayn al-Abidin and dated A.H. 1018 (1609/10 A.D.). The palace behind the Rao captures in the top centre the exterior of the Badal Mahal as it must have looked in the 1620ies. This view has not changed much to this day. Noteworthy is the Deccani shawl waved by an attendant standing behind the ruler. This royal insignia for a while replaced the more customary chamara or chauri, a frond made from the tail of the white yak. Rao Ratan, it must be remembered, received the title of Ram Raj, a unique and high Deccani distinction which the emperor probably created for his loyal Bundi ruler after the latter gallantly defended Burhanpur (district Burhanpur, Madhya Pradesh) against the armies of Malik Ambar (1549-1626), the Prime Minister of Ahmadnagar.

As much as the illustrations in the Imperial Akbar-Nama, the Jahangir-Nama or the Shah Jahan-Nama are based on recorded historical events, as much are the depictions of the sports and pastimes reflections of the Rao’s lifestyle in the third level (C). Perhaps the most arresting composition, situated on the Northern wall just above the mural of Raga Bhairava includes the frontal view of a huge elephant, of which all four legs are visible, including the tail between the hind legs [fig. 3]. The most ancient available rendering of a frontally shown elephant and its mahavat dates from the second century BC. It is a centrally positioned medallion on a stambha of the vedika around stupa no.2 in Sanchi (district Raisen, Madhya Pradesh), which also displays all four legs with the tail in the centre. Since the artist at Bundi was probably not aware of this early example, we have to look at more closer examples. One of them is provided by a spectacular painting from the Jahangir Nama, now folio 21 recto as part of the St. Petersburg Muraqqa’, which is said to illustrate the festivities on the occasion of the accession of emperor Jahangir. Painted by the leading Imperial artist, Abu’l Hasan Jahangir Shahi, it was described by the late Stuart Cary Welch as follows: “Few Mughal paintings outrank this one, which leaps from the page. The picture is alive with innovations, such as the boldly conceived frontal view of an elephant bearing kettle drums.”

The frontally shown elephant in the Badal Mahal is surrounded by baby elephants which seem to be drawn from life. Their movements are so naturalistic and cute that Walter Elias Disney (1901- 1966) would have enjoyed seeing them. This high degree of naturalism, paired with a feeling for a dramatic situation is considered by a later drawing done in the Bundikalam [Front Cover (detail) and Catalogue no 5. page 29]. Here, the elephant does not just stand or trot, it is shown running after a horseman who is already in the grip of the animal’s pro- boscis. This outstanding drawing needs some explanation, which is offered by another detail of level (C) in the Badal Mahal, situated on the Southern wall, right above the entrance [fig. 4]. It has to be noted that in the wall painting as well as the drawing neither mahavat nor horseman (“sowar” in the following quotation) are in battle dress. Elephant and horseman perform a dangerous kind of skill test, an entertainment of which we have close eyewitness reports from the 19th century.

Figure 4

On November 15th, 1875, at 5 p.m., the Prince of Wales (Albert Edward, who was to become Edward VII of the United Kingdom and Emperor of India, r. 1901-1910) visited the Agga [arena for wild-beast combats] of the Gaekwad of Baroda. After watching an elephant fight which his host, Maharaja Sayajirao Gaekwad III (r.1875-1939) arranged for his Royal guest, William Howard Russel (1820-1907), the Irish reporter of The Times who officially accompanied the Prince, notes:

“The prettiest little entr’acte followed this combat. Just as a third elephant was led out and provoked to a proper state of indignation and temper, a lithe compact sowar, mounted on a croppy little horse, with a jerky action and a jaunty step, came into the arena. The cavalier perked up to the beast, which stood balancing itself, now on one leg, then on another, and flopping its proboscis about angrily. There is a strong antipathy between horse and elephant, but the horseman cantered his steed close up to the brute in a very confidential manner. The elephant appeared to take no notice of the sowar, who had not even a whip, and guided his horse by hand and the stirrup-irons. Suddenly the elephant uttered a short, sharp trumpet-note, and made a furious rush at his tormentor. It seemed as if man and horse must die. The end of the proboscis was all but on the rider’s shoulder; a murmur ran round the arena – a cry of horror – which was changed into a burst of applause – as the sowar, with a plunge of the sharp edge of his stirrup-iron, shot away, wheeled round, and, before the elephant could get himself together again, was capering provokingly at his flank. Again and again the scene was repeated, till the elephant was not able to run, but the sowar was never so near capture afterwards. Every one admired his perfect coolness and horsemanship; and when the elephant was fairly tired out, his victor rode away among renewed plaudits. Not always is it so: sometimes the rider and horse are overthrown; and we were told of horses trampled to death, and of riders only escaping by getting between the elephant’s tusks.”

The mural in the Badal Mahal [fig.4] illustrates the successful horseman, whereas the drawing exemplifies a very dangerous moment of the sowar who tries to plunge his push-dagger into the trunk of the elephant in order to safe his life. Another dangerous situation involving an elephant is represented on the Eastern wall, level (C) of the Badal Mahal, [fig.5]. It’s rendering is too well done to be just a product of the artist’s imagination. What happened?

The centre of the Eastern wall shows a combat of two huge dark elephants. This fight is being observed by Rao Ratan and a large amount of courtiers, seated safely on elevated, solid platforms, tribunes, so to say, accessible only by a flight of stairs. The apparent safety of these elevated stands, however, is suddenly no longer guaranteed, as one of the fighting elephants is not impressed by the flight of stairs. The animal, by mounting the stairs, suddenly gets on one of the visitor’s grandstands, his trunk wiping off the unarmed spectators from the platform. Several visitors literally fly in horror, breaking their skull when dashing on the ground.

These few examples alone account for the great spiritedness in depicting dramatic situations on behalf of the artists working for the rulers of Bundi. The murals in the Badal Mahal constitute the cradle of a later offshoot of the Bundikalam, the style of Kota, a state separated by Imperial decree from Bundi, following the demise of Rao Ratan, a ruler with taste.

If you would like to stay up to date with exhibitions and everything else here at Prahlad Bubbar, enter your email below to join our mailing list